Free boundary problem

In mathematics, a free boundary problem is a partial differential equation to be solved for both an unknown function u and an unknown domain Ω. The segment Γ of the boundary of Ω which is not known at the outset of the problem is the free boundary.

The classic example is the melting of ice. Given a block of ice, one can solve the heat equation given appropriate initial and boundary conditions to determine its temperature. But, if in any region the temperature is greater than the melting point of ice, this domain will be occupied by liquid water instead. The location of the ice/liquid interface is controlled dynamically by the solution of the PDE.

Contents |

Two-phase Stefan problems

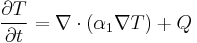

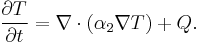

The melting of ice is a Stefan problem for the temperature field T, which is formulated as follows. Consider a medium occupying a region Ω consisting of two phases, phase 1 which is present when T > 0 and phase 2 which is present when T < 0. Let the two phases have thermal diffusivities α1 and α2. For example, the thermal diffusivity of water is 1.4×10−7 m2/s, while the diffusivity of ice is 1.335×10−6 m2/s.

In the regions consisting solely of one phase, the temperature is determined by the heat equation: in the region T > 0,

while in the region T < 0,

This is subject to appropriate conditions on the (known) boundary of Ω; Q represents sources or sinks of heat.

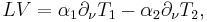

Let Γt be the surface where T = 0 at time t; this surface is the interface between the two phases. Let ν denote the unit outward normal vector to the second (solid) phase. The Stefan condition determines the evolution of the surface Γ by giving an equation governing the velocity V of the free surface in the direction ν, specifically

where L is the latent heat of melting. By T1 we mean the limit of the gradient as x approaches Γt from the region T > 0, and for T2 we mean the limit of the gradient as x approaches Γt from the region T < 0.

In this problem, we know beforehand the whole region Ω but we only know the ice-liquid interface Γ at time t = 0. To solve the Stefan problem we not only have to solve the heat equation in each region, but we must also track the free boundary Γ.

The one-phase Stefan problem corresponds to taking either α1 or α2 to be zero; it is a special case of the two-phase problem. In the direction of greater complexity we could also consider problems with an arbitrary number of phases.

Obstacle problems

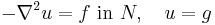

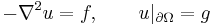

Another famous free-boundary problem is the obstacle problem, which bears close connections to the classical Poisson equation. The solutions of the differential equation

satisfy a variational principle, that is to say they minimize the functional

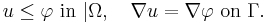

over all functions u taking the value g on the boundary. In the obstacle problem, we impose an additional constraint: we minimize the functional E subject to the condition

in Ω, for some given function φ.

Define the coincidence set C as the region where u = φ. Furthermore, define the non-coincidence set N = Ω\C as the region where u is not equal to φ, and the free boundary Γ as the interface between the two. Then u satisfies the free boundary problem

on the boundary of Ω, and

Note that the set of all functions v such that v ≤ φ is convex. Where the Poisson problem corresponds to minimization of a quadratic functional over a linear subspace of functions, the free boundary problem corresponds to minimization over a convex set.

Connection with variational inequalities

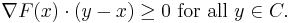

Many free boundary problems can profitably be viewed as variational inequalities for the sake of analysis. To illustrate this point, we first turn to the minimization of a function F of n real variables over a convex set C; the minimizer x is characterized by the condition

If x is in the interior of C, then the gradient of F must be zero; if x is on the boundary of C, the gradient of F at x must be perpendicular to the boundary.

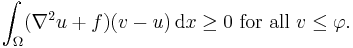

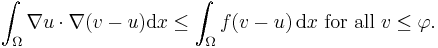

The same idea applies to the minimization of a differentiable functional F on a convex subset of a Hilbert space, where the gradient is now interpreted as a variational derivative. To concretize this idea, we apply it to the obstacle problem, which can be written as

This formulation permits the definition of a weak solution: using integration by parts on the last equation gives that

This definition only requires that u have one derivative, in much the same way as the weak formulation of elliptic boundary value problems.

Regularity of free boundaries

In the theory of elliptic partial differential equations, one demonstrates the existence of a weak solution of a differential equation with reasonable ease using some functional analysis arguments. However, the weak solution exhibited lies in a space of functions with fewer derivatives than one would desire; for example, for the Poisson problem, we can easily assert that there is a weak solution which is in H1, but it may not have second derivatives. One then applies some calculus estimates to demonstrate that the weak solution is in fact sufficiently regular.

For free boundary problems, this task is more formidable for two reasons. For one, the solutions often exhibit discontinuous derivatives across the free boundary, while they may be analytic in any neighborhood away from it. Secondly, one must also demonstrate the regularity of the free boundary itself. For example, for the Stefan problem, the free boundary is a C1/2 surface.

References

- Alexiades, Vasilios (1993), Mathematical Modeling of Melting and Freezing Processes, Hemisphere Publishing Corporation, ISBN 1560321253

- Friedman, Avner (1982), Variational Principles and Free Boundary Problems, John Wiley and Sons, Inc., ISBN 9780486478531

- Kinderlehrer, David; Stampacchia, Guido (1980), An Introduction to Variational Inequalities and Their Applications, Academic Press, ISBN 0898714664

![E[u] = \frac{1}{2}\int_\Omega|\nabla u|^2 \, \mathrm{d}x - \int_\Omega fu \, \mathrm{d}x](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/8b4f5e45124b54e37af35d57f1d0c598.png)